The Rise and Fall of Blue-Collar Welland

The Rise and Fall of Blue-Collar Welland

Welland, a small industrial city in the Niagara region of Canada, is home to approximately 54,000 residents. It is also home to a rich history: a story of boom and bust, exploitation and resistance, poverty and prosperity.

The city was first named Aqueduct, then Merrittville (or Merrittsville) in 1842, and finally Welland in 1858. Many communities, such as Crowland and Dain City, united to become Welland as we know it today. Throughout its history, the city and the lives of its people have been tied to the development of the various canals, and the industry and jobs that followed. Between the 1820s and today, the canals have changed from wood, to stone, to reinforced concrete; while the vessels have gone from sailing ships, to steam-powered propellers, to large, modern bulk carriers.

Welland is built on the backs of generations of blue-collar workers and their families, many of them from diverse immigrant communities. From the treacherous digging of the canals and fatalities that occurred, to the war manufacturing booms, to the mass unionization of workers and the later deindustrialization, The Rise and Fall of Blue-Collar Welland explores the history of Welland through the lives of its hardworking people.

Welland Through the Years

The Beginning of Welland

1824-1850s

The beginning of what would later become Welland started with the construction of the first canal between Lake Ontario and the Niagara River– extended to Lake Erie in 1833– and the Second Canal, which was finished in 1845. One of the settlements that arose along the canal was called Aqueduct, known today as Welland.

Why a Canal?

In the early 1800s, Canada was a developing nation. We had just made it through the war of 1812, and the resulting atmosphere of competition with–and fear of– our American neighbours created the perfect conditions for industrial development.

Canals symbolised advancement; ushering in the urban, industrialized future, and a canal connecting the two great lakes had been suggested as early as 1699. A trade route across the Niagara Peninsula would encourage population growth, trade, and economic activity, and allow Montreal to compete with New York City. Additionally, building the canal inland would make it defensible against any future American attack, and it could bypass the treacherous Niagara Falls.

How was the Canal Funded?

The Welland canal came to fruition as a result of the determination of a man named William Hamilton Merritt. He was the founder of the Welland Canal enterprise, and began promoting the project as early as 1818. Merritt was so dedicated to the building of the canal that he visited England to raise funds for it. Due to his efforts, some British investors contributed to the canal enterprise and made the construction of the Welland Canal possible.

The rest of the funds came from the government of Upper Canada, and individual contributions from New York, Upper Canada, and Lower Canada. Because of Merritt’s significance in the development of the Welland Canal, Aqueduct was renamed to Merrittville (or Merrittsville) prior to becoming Welland. By the year 1830, the town had a plot of 75 acres.

Working on the Canal

With the funding and planning for the canal taken care of, it was time to start on the construction. Workers from across Canada and the world came to Niagara for the opportunity to work on this huge project, but it was a difficult and sometimes treacherous job.

Canal workers suffered from various diseases such as cholera and typhoid due to the marshy work conditions and lack of potable water. In fact, it was the job of ‘water-boys’ to deliver whiskey to the working men in tin pails to quench their thirst. Some workers suffered accidents or even died– such as when the banks of the trench collapsed in 1828–and they often had to wait weeks or months to be paid. In the summer of 1842, 2,000 canal workers marched into St. Catharines on strike, demanding work for all. Posters along the canal read “Death and vengeance to any who should dare to work until employment is given to the whole.”

The First Canal

The Welland Canal gets its name from the Welland River, which was originally going to be the water source for the canal. However, they opted to use the Grand River instead. After the canal was built, small towns sprung up along its path to house the workers and cater to their needs. The use of a towpath also contributed to the development of towns, as the teams of horses and oxen that towed sailing vessels along the canal needed to be stabled, fed, and shod.

With the memory of war still fresh, the canal’s depth and width were increased from the original plans, allowing for the transport of gunboats. Luckily, the precaution was unnecessary and in 1829, the first two vessels passed upstream through the canal with Merritt on board. It was soon extended all the way to Lake Erie, opening in 1833.

The Second Canal

In 1837, a report showed that the private Welland Canal Company was losing over $14,000 a year maintaining the canal, and in 1841, Upper and Lower Canada were unified. This led to the Province of Canada building a second canal, one that was larger with stone locks instead of timber, and a more direct route: between Port Dalhousie on Lake Ontario, and Port Colborne on Lake Erie. The improvements on this canal followed technological advancements in vessels, with the introduction of small metal-hulled steam vessels.

Where Rails and Water Meet

1850s-1900

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the introduction of railroads and the construction of a third canal brought change to Welland. Fluctuations in prosperity and poverty of the town fostered both growth and unionization.

The Third Canal and the Railroads

As railroads became a more popular mode of transportation, they were introduced to Niagara. Seven railroad lines were built across the peninsula between 1853 and 1911, with the Welland Railway running parallel to the canal. Since railroads were quickly becoming the preferred mode of transportation, they could have posed a serious threat to the Welland Canal.

Fortunately, in Welland the canals worked in conjunction with the railways instead, furthering prosperity in the town instead of hindering it. The vessels using the canal even started to be towed by steam tugs instead of horses or oxen. During this time the Third Canal was constructed, and was completed in 1887.

Map of Welland, 1876

Map from Welland Museum archives, scans from Brock University.

Prosperity & Struggle

No longer a small collection of workers’ dwellings and shops, by 1851 Welland’s population had grown to 1500 people. This was decently large for the time; for comparison St. Catharines had 3400 people and Port Colborne had 160 in the same time period. Quotes from local newspapers at the time illustrate the prosperity of the region: in 1878 the Tribune printed “Welland is the liveliest town in Canada”, and The Telegraph in 1887 insisted “Never before in its history has Welland displayed such a spirit of enterprise.”

As good as times were, however, they didn’t last long. While in 1881 Welland is recorded as having 53 industries, that number would drop by 17 down to 36 industries just ten years later. This loss and resulting economic hardship can be attributed to a couple factors. When the Third Canal was completed in 1887, large numbers of construction workers that had been working on the canal suddenly left Welland. In addition to this loss, the economy went into recession in 1891.

The Beginning of Unionization

One of the recurring themes in the story of Welland and its blue-collar workers is the power of unionization and community. At this time in Welland’s history workers started to realise the power of organization, and set the foundation for years of striking for– and winning– workers’ rights. In 1860 the wages for canal diggers were only 90 cents per day, and workers spent the next forty years trying to raise wages to over a dollar a day. In 1874, workers on sections 29 and 32 of the Welland Canal went on strike for higher wages, and in 1878 the stonecutters went on strike.

Instead of coming to a deal with the stonecutters, their company (the one supplying concrete for a new bridge) imported workers from Buffalo. The Tribune covers this strike on March 8, 1878:

“Owing to the small force employed, and the large number of unemployed men lying around, the strike was a failure here. The places vacated by the few men who struck were promptly filled by others willing to work at the old rates.”

In the 1880s an organization called the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor arrived in Niagara, meaning ‘unskilled workers’, including women, could now join the labour movement. People jumped at the opportunity, and over two thousand workers established twenty-three locals in the Niagara Peninsula.

Watch Welland Grow

1900-1930

The Welland Ship Canal

The Third Canal, whose construction had taken the last part of the nineteenth century, was already out-of-date and unequipped to handle traffic and volume demands by 1907. The solution: another canal. The fourth canal, the Welland Ship Canal, began construction in 1913. The Welland Ship Canal Construction Railway was built to assist in the construction of the fourth canal, and was in operation between 1913 and 1934. After a brief pause in construction during World War I, the canal opened in 1932.

People working on the construction of the canal could expect accommodation in workers’ camps, with sleeping and dining facilities, good food, electricity, and a small store. However, the lack of recreational facilities led to a moral panic over how the workers spent their free time; reportedly in search of alcohol and getting into fights. This caused missionaries and missionary organizations to get involved, building ‘reading and recreation rooms’, which were also used to hold religious services.

Despite the relatively good living conditions, the work was still dangerous, and the handling of accidents and land takeover morally questionable. Recent research has found that 137 men died during the construction of the Welland Ship Canal between 1914 and 1932, and that the land from many established farms and one family burial ground was taken for the canal.

Why Welland?

“WELLAND DREAM: when we get all these big concerns—the steel plant, sugar factory, Bertman’s ship yards, and the Deering Farm Implement Factory, we shall have a second Toronto.” – the Telegraph, February 1921

Although it may be hard today to compare Welland to cities like Toronto or Montreal, there were many factors that drew people and industries to Welland and made it an important city in the early 1900s. Welland had the canal and railways, it was close to the U.S. border, inexpensive hydroelectric power was available from Niagara Falls and DeCew Falls, the climate was moderate compared to the rest of Canada, and even if there weren’t any industry jobs available there was seasonal employment available in agriculture and construction.

Population Boom

During 1906-1907 and 1911-1913 many factories relocated to Welland-Crowland (Welland), and the population exploded. The population of Crowland doubled in 1913, and Welland almost doubled in population in 1907 and doubled in 1913.

Despite its prosperity and growth, a lot of the tax money was never invested into the community. Factories were given free improvements using tax dollars, and many of the profits made in the local factories were exported untaxed to New York and other places. This meant that things like education and healthcare facilities, parks, and recreation were underfunded, and it has been said that “ditches lined the streets and smoke blackened the air.”

Unionization & Poverty

The blue-collar workers of Welland continued to unionize and strike for a better life during this time. One of these strikes is reported in the Telegraph on May 15, 1914:

“For the first time in the history of Welland, a force of unemployed have demanded work. At 9:00 AM Thursday May 14, a small army of men 200 strong, marched down South Main Street to the town hall, and general spokesmen stated to the Chief of Police that they must have work or starve.”

The strike was successful, with the newspaper reporting days later on May 19:

“The Mayor heard of their complaints and demands, and enquiring into the case found that they were only too well-founded. Whole families had been existing for weeks on one meal per day, some had no food for a couple of days. A promise was made to provide food until they could find work or leave town.”

The Great Depression, War & Unionization

1930-1960

The Crowland Relief Strike

During the years of the Great Depression, many people had to apply for relief to be able to survive. In Crowland 1,000 individuals were on relief, and 1,500 in Welland. In Crowland, the male head of the family could work for the town building sewers in exchange for food, shelter, medical aid and clothing for their families.

Working for their relief was supposed to preserve the men’s dignity, but in 1935 they learned they would have to work longer hours to qualify. Feeling as though they were being taken advantage of, they went on strike. The whole community came together in support of the strikers in this difficult time, donating food and used clothing to keep them going. Eventually concessions were made to the strikers, and they returned to work.

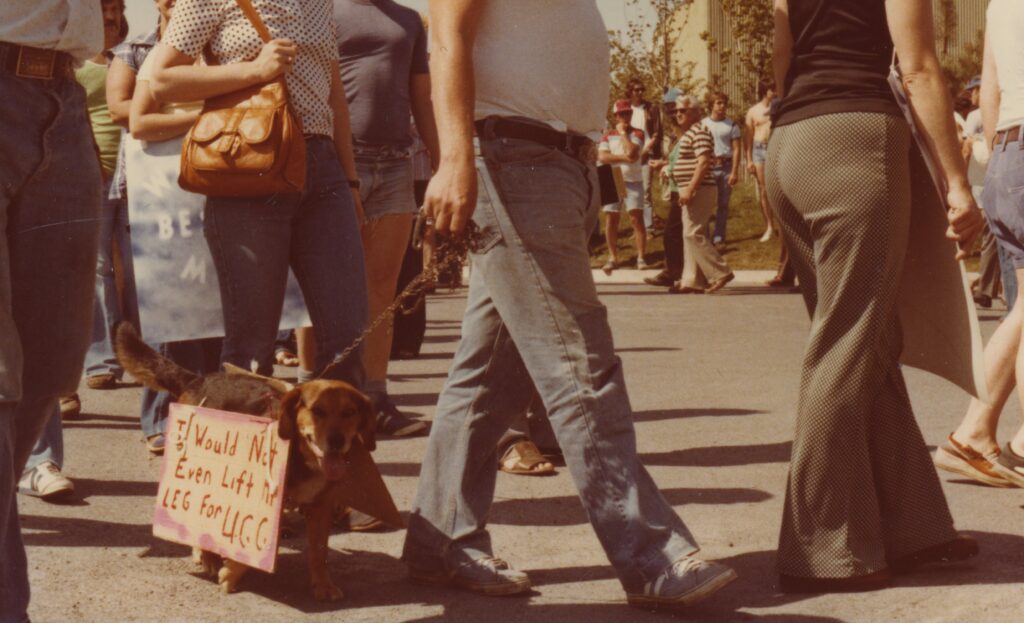

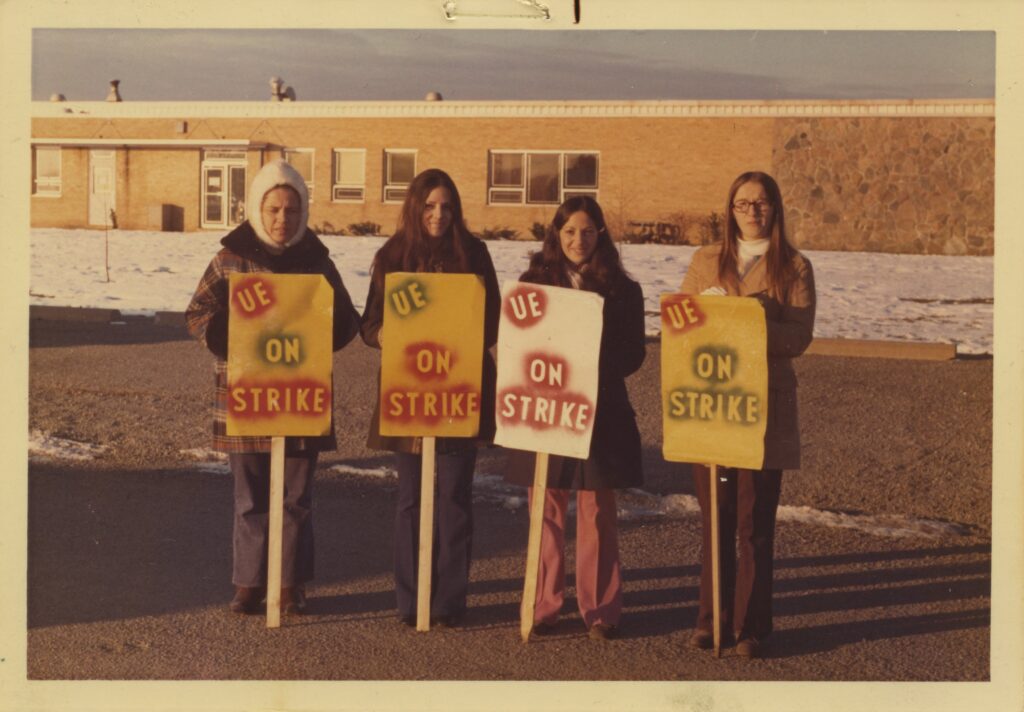

The UE

After the hardships of the Great Depression, there was increased interest in unionization. In 1942 the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers Union, also known as the UE, started to make its way into Welland industry.

This union was particularly successful among immigrants, who faced discrimination and language barriers in the workplace on top of the usual issues of little pay and long hours. In fact, it has been recorded that one UE meeting in Hungarian Hall was so packed that the president of the UE had trouble getting through the crowd inside. Beyond the benefits in security and money, unionization gave people a chance for dignity and self-respect that they hadn’t had access to before.

The Great Depression and Wartime Boom

In the 1920s, particularly 1926-1929, Welland’s economy was booming. However, as always, it did not last. An economic crash and the Great Depression that followed hit Canadians hard, and it was no different in Welland. The situation was so desperate that many of the malnourished children of the depression were declared physically unfit to serve in World War II. In the decade following the crash, hundreds of unemployed workers would line up at factory gates every day, hoping for work.

Luckily for Welland, the outbreak of World War II was a great opportunity for towns built on industry. The sudden increase in demand for their products meant that by 1940 the factories were employing everyone they could and still needed more workers. Atlas Steels in particular grew exponentially, employing 3,000 people. This demand for workers caused a population increase of 10,000-15,000 people in Welland and 5,000-10,000 in Crowland, a massive amount with which housing could barely keep up.

Pages from This is Welland brochure (1950s). Welland Public Library.

Of course, this large influx of people meant that when the war was over and demand decreased again, many people were left without work. The threat of a second depression did not last long though, as the U.S. entered the Korean civil war in 1950 and manufacturing was once again in demand. Thanks to a second wartime boom and the success of unionization, by the 1950s Welland and Crowland had some of the highest labour wages in Ontario.

Welland on the Rise

1960-1980

Watch Welland Grow

The growth of the 50s continued for the latter half of the 20th century, with several reports and advertisements from the 70s boasting of Welland’s success and prosperity. In 1970 different parts of Welland County came together to form Welland as we know it today, and a year later the population growth rate was recorded at 22%, significantly higher than Toronto’s 3.79%. By 1977 the city had a population of between 45 and 46 thousand, with 27 public schools and 375 acute-care beds in Welland County General Hospital. An advertisement for the City of Welland in 1977 states:

“Contrast is so appropriate for describing Welland’s attractiveness: Because our beehive of industry is contained in a city noted for its fine homes and institutions, neat and pleasant subdivisions, and outstanding educational facilities, concert and theatre organizations, and festival-minded people of many races, most of whom love to grow roses. A city where modern malls, plazas and a refurbished downtown core cater to shoppers and offer full and professional services.” Another says “…we’re close to realizing the long-standing ideal of a modern and sophisticated city, not large in size, but large in its ability to serve its people and its industry and to provide a pleasant and rewarding place for both.”

Pages from the Welland City Brochure (1970). Welland Public Library.

Welland was an up-and-coming city, a prosperous centre for industry that was ranked above Hamilton in a list of industrial growth points. In the 70s the city had the third highest labour income in Ontario, 14% above the national average, and had the highest disposable income in Niagara.

The Bypass

The growth of Welland was so great during this time that the volume of land traffic and water traffic inconvenienced each other at crossing points. The solution to the problem, completed in 1973, was a by-pass around the city of Welland, going directly from Port Robinson to Humberstone. The new section was 350 feet wide at the bottom, where the old one was 192 feet, and the project cost more than $110 million. What they didn’t realize at the time was that the removal of such an important feature of Welland would have consequences in the future.

More pages from the Welland City Brochure (1970). Welland Public Library.

Welland’s Renaissance

1980s

“The City is certainly on the threshold of a new spirit and optimism for the future as evidenced by the increase in building permit values for the fourth consecutive year and the many new business openings. I hope you share our optimism for Welland’s econmic future.”— (Welland Development Commission Annual Report, 1987)

Welland’s good fortune continued well into the 1980s: it was a time of industrial, commercial and residential expansion, and the future looked bright. This prosperity is demonstrated by a summary of the information presented in the Welland Development Commission’s Annual Reports in the years 1987, 1988, and 1989.

Warning Signs

Around 1989 Welland’s good fortune started to decline. Suddenly major companies were laying off employees, totaling between 369 and 394, after years of high rates of residential growth.

This was just a taste of what was to come, and it was caused by several coinciding factors. The Canadian economy slowed down, with the growth rate expected to slow to 1.6 percent in 1990, and many people were worried about the risk of recession. One of the major industries in Welland, Atlas Steels, was sold to the Sammi Group of South Korea and was suffering from the federal government’s trade sanctions with South Africa, a supplier of chromium. Critically, NAFTA was introduced, and globalization and free trade brought with it concerns of out-competition.

Life After Industry

1980s-2000s

Deindustrialization

“…the case of Welland demonstrates all too well the problem of allowing a community to become hostage to a callous and indifferent free market system that allows companies to treat workers and their communities as expendable vessels in the unapologetic pursuit of profit.”

Foreshadowed in the late 1980s, Welland’s situation worsened in the following decades. The introduction of free trade in the 1980s and a decline in unionization contributed to a wave of deindustrialization that devastated the city at the turn of the 21st century. Many industries relocated to places with cheaper, non-unionized labour, and the de-regulation of electricity caused fluctuations in energy cost that drove companies away. The steel industry in Ontario, one that formed a large part of the industrial sector in Hamilton and Welland, was particularly hard-hit.

In the ten years between 1991 and 2001, approximately six thousand manufacturing jobs were lost to plant closure and downsizing, and in 2000 the Canadian Labour Council published a “communities in crisis” report featuring Welland as a case study. In 2008 and 2009 the community received another huge blow: the John Deere plant was closing, costing Welland 800 jobs. According to a CTV news article, the company said it was “consolidating its manufacturing operations to improve efficiency and profits, and the work will be moved to plants in Wisconsin and Mexico.” At the time, NDP candidate Malcolm Allen and NDP leader Jack Layton attributed the John Deere closure to free trade and the government’s lack of industrial policy.

Welland Today

2024

Welland’s Challenges

In order to face the future in a productive way, it is important to be realistic about where Welland stands today. There is no denying that Welland and its people have many challenges to face; decline in manufacturing jobs, high unemployment rates, and youth leaving the city in search of work are all obstacles we must overcome. However, thanks to the hard work and optimism of Welland’s citizens, as well as the many assets Welland has to offer, there are no obstacles that can’t be overcome.

The Future

“Welland’s assets are not only trucks, machinery, snowplows, buildings etc., but also the talented community; the people of Welland. The youth, locally educated and looking for work.”

While it may not be the industrial centre that it once was, Welland has much to offer. It boasts a skilled labour force, a Niagara College campus, cheaper housing than elsewhere in Ontario, a comparatively mild climate, less traffic than other parts of Niagara and the Greater Toronto Area, and it’s within easy driving distance to big cities such as Toronto, Hamilton, and Buffalo NY. Additionally, Welland is the only city on the Welland Canal that owns waterfront canal land that can be modified for its use.

Many community members are passionate about the revitalization of their city, and have made suggestions for the future of Welland which range from event and festival promotion, to turning a section of the canal into the world’s largest goldfish pond!

Meet the Companies

The companies that employed thousands of people and engaged in power struggles with their lower-class workers are an integral part of Welland’s history. Whether by enriching the community or exploiting their employees and driving them to unionization, these corporations made our city what it is today.

Atlas Steels

Atlas Steels was a major company, and extremely influential in the history of Welland. It benefited more than most companies from the production boom during World War II, and quickly became massive. In 2000 it was purchased by Slater Steel, but declared bankruptcy and closed in 2004. It was then bought by MMFX Technologies Corporation of California, and reopened as MMFX Steel Canada. A year later, it went into bankruptcy and closed again. Recently, previous Atlas Steel manager Tim Clutterbuck bought it and established ASW, which is still in operation today.

Unionization

From 1935, before the introduction of the UE in Niagara, the Atlas Steels Employees’ Association was responsible for their workers’ social and recreational activities. Perhaps to keep up with the unionization craze sweeping Welland, in 1942 the Association became the Atlas Workers’ Independent Union (essentially a company union) that was able to bargain with Atlas Steels on behalf of the employees.

However, Atlas Steels workers voted 1,263 to 110 in favour of being represented by the UE instead. Atlas Steels refused to recognize the UE as representative for their workers, claiming they had already signed a contract with the Independent Union.

This was the last of many desperate attempts. To prevent the vote going against their favour they had already fired UE activists, delayed the elections by three weeks, and refused to allow the election to take part on the company premises. They also bribed workers with $20, which in 2023 would be approximately $357, announced wage increases just before the vote, and placed uniformed company policemen at the door of the polling station to intimidate workers.

The Karsh Portraits

“I have sought to portray the dignity, the pride of workmanship, the sense of independence I have found in these steelmen who work with their brains and their hands in a free economy under a democratic form of government…They had a joy in working which transcended even the very excellent pay they receive at the end of each week.” – Yousuf Karsh, photographer (1950)

When faced with the prospect of their employees unionizing, Atlas Steels started a publicity campaign to counter ideas of organized labour with an emphasis on individualism and pride. Through a New York public relations company, a photographer named Yousuf Karsh was hired to photograph a series of worker portraits titled ‘The Men Who Make Atlas Steels’. These photographs were exhibited in Welland where relatives of the men featured could admire them, and were presented to the workers’ wives by the Atlas president R.H. Davis. He told them how proud he was of their husbands, a continuation of the campaign’s presentation of him as a ‘plant man’; a man respected by the company’s blue-collar workers.

Health Concerns

Unfortunately, Atlas Steels was not always a safe place to work. In Hamilton, it was discovered that people who spent time in the melt shop in steel plants were at a higher risk for developing cancer. The study was repeated in Welland at Atlas Steels, and out of the 368 employees studied 30% died of cancer, higher than the Ontario average. That increase in cancer deaths is attributed to respiratory cancers.

Beatty and Sons Foundry and Machine Shop

“The contemplated removal of Messrs. Beatty and Sons is a serious matter for Welland. We understand that St. Catharines will exempt them from taxation for ten years if they locate there. We are opposed to the principle of exemptions or bonuses of any kind and think they should be forbidden by law, but now we must take things as we find them. Will it pay to let other places absorb the very life blood of the town?” – The Tribune, April 25, 1884

Beatty and Sons Foundry and Machine Shop was Welland’s first major industry, but as is evidenced by the above quote from The Tribune in 1884, they became greedy. The company threatened to move out of Welland to St. Catharines unless they were granted tax exemptions, putting the people of Welland in a difficult situation: should the community give the rich corporation tax exemptions, or lose good jobs?

Empire Cotton Mills

Empire Cotton Mills was an extremely influential company in Welland’s industrial history, and a notoriously bad employer. It attracted many French Canadians to the city, developing Welland’s francophone community, but poor working conditions and low wages drove their employees to some of the most powerful labour organization Welland has seen.

Immigrant Communities

Empire Cotton Mills is well-known for its French employees, the origin of the Francophone community in Welland. In 1914 it was bought by a company based in Quebec, and they brought twenty francophone families to work in the factory. Then during the second World War, the company (at that point the Woods Manufacturing Company), was in need of part-time employees. They brought in Chinese people from British Columbia, French from Quebec, and Ukrainians from Saskatchewan. They also employed immigrant women as well as men, which was unusual at the time.

Strike of 1936

“French, Hungarian, Ukrainian, Polish, Italian and English workers picketed the plant 24 hours a day. Through mid-winter weather, below zero and in two feet of snow, pickets stalked the mill. They huddled along the railway fence using crude tin shelters and tin can stoves.”

In 1936, Empire’s employees were fed up with their treatment. There had been wage cuts that left many employees unable to support their families, despite sixty-hour weeks. Most of them lived in company housing, and after having the rent deducted from their pay, they couldn’t afford food. Part of the problem was that they were paid based on the amount of product they produced, not by the hour, and they were often fined for the poor quality of products– when in reality the materials they were provided were of poor quality.

| Married men with families | Weavers with 9 years’ experience | Boy spinners | |

| Hours/Week | 60 | 50 | |

| Pay/Week | $8 or $9 | $9 | $8.35 |

On December 22nd, 1936, 865 Empire Cotton Mill textile workers walked off the job in a strike that would last 42 days. They demanded a 20% increase in wages, shorter hours, good quality cotton to work with, proper ventilation in the mill to ease respiratory issues, and the right to be represented by The United Textile Workers of America.

The very first night of the strike 88 of the strikers were fired, and another 100 were fired the next day. Despite this drastic action, the workers were determined. They picketed 24 hours a day, and were able to stop shipments of materials into the plant. The general manager at the time, Nelson Batchelder, did not respond well to this labour action. He wanted provincial policemen to be called to Welland to put down the strike, and only begrudgingly accepted the recommendations of the Ontario Department of Labour to deal with the situation.

He immediately broke his promise to not discriminate against any of the strikers upon their return to work, firing and blacklisting them so they could not find work at any factory in the city. It wasn’t until ten years later, in November of 1946, that the cotton mill workers won the right to be represented by UTWA Local 155.

“the people could speak up when they didn’t like something. Because before, if you—anyone—spoke up, the next day you noticed that you no longer had…your punch card. You could go home.” — Stephen Bornemissza, Empire employee, on unionization

John Deere

Nothing Runs Away Like a Deere

“One of mankind’s most pressing problems today is providing food for our rapidly growing world population. Here, at the John Deere Welland Works, we are making a positive contribution to the solution of that problem. Since 1910, our factory has been producing high quality farm equipment to help the world’s farmers multiply their productivity. Today, more than 80 percent of our production is exported to farmers in many different countries around the world. The wide variety of machines designed and manufactured at the Welland Works includes loaders, spreaders, blades, wind-rowers, disk tillers, offset disk harrows, forage wagons, rotary cutters and wagon running gear.” -–advertisement for John Deere Welland Works, 1977

The John Deere factory in Welland, in operation since 1910, provided many families with income and the community with taxpayer money for almost 100 years. It was an integral part of Welland until the early 2000s.

In 2008 John Deere announced that it would be closing its Welland location by the end of 2009, causing 800 people to lose their jobs. This came as a huge shock to the community: there had been no warning signs. The company said “the decision is not a reflection of the work or productivity of our employees” (2), and blamed the high exchange rate and increasing energy costs for the move.

“Things like dry cleaners, or restaurants, or coffee shops—private services. Even public services, like schools and hospitals, depend on us having a strong manufacturing foundation. Otherwise there is nobody there to pay the taxes that support those other jobs. So, for every job that is lost in manufacturing, there are three or four or five jobs elsewhere in the economy that also disappear. That is why our entire community is at stake here.”

–Jim Stanford, CAW Chief Economist

The closure of John Deere was devastating for Welland: foodbank demand suddenly increased, infrastructure and social programs suffered a loss in taxpayer money, charities couldn’t reach their fundraising goals, and the families of those 800 workers suffered immensely. People were understandably angry, and a twist on the company’s slogan became popular: “Nothing runs (away) like a Deere”.

Page-Hersey Iron Tube and Lead Company

One of the major industrial companies operating in Welland was Page-Hersey Iron Tube and Lead Company. Page-Hersey move to Crowland in 1907, and began operating in 1910. Page-Hersey was bought by Stelco in 1965 along with Welland Tube Works, and in 1985 they were both incorporated under the name Stelpipe.

Page-Hersey Strike

Like most of the companies mentioned so far, Page-Hersey’s employees improved their working conditions via labour action. On September 26th, 1935, Page-Hersey workers went on a strike lasting 11 days. The employees asked for a 25% wage increase, from 30 cents an hour to 37.5 cents an hour.

Page-Hersey offered a 5% wage increase, to 31.5 cents an hour, and “the privilege of working a nine-hour day”. The workers refused, and the next day the plant was closed and all the gates picketed. They formed their own union, ‘Workmen’s Union of Page Hersey’, and 600 strikers paraded in a demonstration from the Market Square to Page-Hersey. The day of the parade, 400 men joined the union.

The strike was finally settled on October 7th, with the wages raised from 30 to 35 cents an hour and a 5% increase for piece work, and the hours reduced from 10 to 9 a day. Page-Hersey signed a six-month contract with the Workmen’s Union of Page Hersey, but a company-affiliated union was also established. The Page-Hersey Company Union was more for show than the workers’ benefit, and by 1943 the workers invited in the UE (United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers Union) instead.

Plymouth Cordage

Plymouth Cordage began in Plymouth, Massachusetts, specializing in rope and binder twine manufacture. It announced its move to Welland in 1905, after the citizens of Welland voted in favour of a tax break for the company. Employees of Plymouth Cordage were able to live in company housing, as long as a member of the family worked there—although this also meant that their housing was tied to their job and company loyalty.

In general, Plymouth Cordage looked after its workers well. The workers’ accommodation included a community hall, a library, a bowling alley, and billiard tables, as well as sewing, carpentry, and cooking classes. Additionally, the company contributed to the community by donating land for a school, contributing funds for a hospital, and donating to the local parks commission and the Methodist and Greek Orthodox churches.

Italian Workers

When Plymouth Cordage relocated from Massachusetts, they encouraged their Italian American employees to relocate with them and bring family members from Italy. They believed this would not only save them the cost of training new employees, but would strengthen their loyalty. It is partly thanks to Plymouth Cordage that Welland has such a large Italian-Canadian population today.

Chinese Workers

In 1917, Plymouth Cordage was losing many workers to better-paid jobs in other factories. Apparently Plymouth’s wages were so low they were “almost scandalous”. (2) Its solution was to employ 200 Chinese workers from other parts of Canada. Chinese Canadian workers were willing to work for Plymouth despite the low wages, because racism prevented them from getting manufacturing jobs elsewhere. Unlike other ethnic groups who stayed in Welland, most of the Chinese workers left after World Wars I and II ended.

Union Carbide

Union Carbide, operating as Electro Metals, the Electro Metallurgical Company, and UCAR Carbon at various points, started operations in 1914 with 300 workers. Eventually its headquarters were moved to Welland in 1991 along with 400 jobs.

An advertisement for Union Carbide in 1977 boasts its productive history in Welland:

“For seven decades: an eye on the future: We began to build our Canal Bank Road plant one spring day in 1907…and we’re still building, because expansions and improvements to our operations are a yearly occurrence. We’ve had an eventful history of progress in Welland…from Canada’s first ferroalloys furnace, which we operated on the initial, 60-acre site…to major contributions in two world wars…and a $12 million development in 1971 that provided one of the world’s most advanced methods of making graphite electrodes for the steel industry. Today, forward-looking projects at the plant include continued installation of the latest and most sophisticated environmental control systems—mainly of our own design—and an expanded health and safety program for our 800 employees. The environment and the welfare of our employees. These remain among our highest priorities as we move into our eighth decade of development.”

1946 Strike

Despite the rosy picture painted by the advertisement, Union Carbide’s and its blue-collar workers had their fair share of struggle.

In 1946, employees asked for a wage increase of 25% and a reduction of the work week to 40 hours through the UE local 523. The company accepted the work week reduction but offered only a 4-cent-an-hour increase, and then 10 cents an hour under threat of a strike. Even the 10-cent increase would only make up half the amount of money lost to the workers by the 8-hour work-week reduction, meaning the deal offered by Union Carbide would realistically reduce take-home pay by $4 per week. To put this in perspective, $4 then is equivalent to about $65 per week or $260 per month in 2023. This deal was obviously unacceptable, and on July 8th , 1,300 Union Carbide employees went on strike.

A chant could be heard from the picket line:

“for twenty years the company has watched us burn, now they can burn while we watch.”

It took ninety-five days for the strike to end, and a delegation of Welland UE members visiting the Department of Labour in Ottawa. The settlement consisted of the forty-eight-hour week being kept, and a wage increase of thirteen cents per hour.

Indigenous Niagara

Indigenous History in Niagara

Long before Welland existed, this land that is now known as the Niagara region was home to the Neutral Nation, Six Nations of the Grand River of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation of the Anishinaabek people. Current archaeological evidence and oral tradition suggest that the land along the Niagara River has been occupied by Indigenous peoples for 13,000 years.

The city of Welland sits on Treaty 3 territory, part of the Between the Lakes Purchases signed on December 2nd, 1792. This treaty was signed by Mississauga peoples and representatives of the British crown, and sold approximately 3 million acres of land to the crown for 1,180 British pounds. To put this into perspective, this would be equivalent to 3 million acres of land in Niagara being sold for $245, 998 today.

Treaty 3 Excerpts

“It was witnessed that the said Wabakanyne and the said Principal Chiefs and Women above named for and in consideration of the sum of eleven hundred and eighty pounds, seven shillings and fourpence of the lawful money of Great Britain, to them the said Wabanyne, Sachems, War Chiefs and Principle Women in hand well and truly did grant, bargain, sell, alien, release and confirm until His said Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, all that tract or parcel of land lying and being between the Lakes Ontario and Erie…”

“To have and to hold all and singular the said tract or parcel of land with is [it’s] appurtenances until His Brittanick Majesty, His heirs and successors forever. And whereas at a conference held by John Russeau, Interpreter, it was unanimously agreed that [t]he King should have a right to make roads thro’ the Messissague Country that the navigation of the said rivers and lakes should be open and free for His vessels and those of His subjects, that [t]he King’s subjects should carry a free trade…in and thro’ the country: Now this Indenture doth hereby ratify and confirm the said conference and agreement so had between the parties aforesaid, giving and granting His said Majesty a power and right to make roads thro’ the said Messissague Country together with the navigation of the said rivers and lakes for His vessels and those of His subjects trading thereon free…”

Broken Promises

When we talk about the history of the Niagara region, one of the first things that comes to mind is the war of 1812. It is widely recognized that First Nations allies made it possible to defend Upper Canada against American forces, and deeply impacted the history of our country. Unfortunately, this demonstration of allyship was not reciprocated by settler Canadians or their government.

The building of the Welland canals, which led to prosperity and growth for many in our community, came at the cost of Six Nations’ land. When the Welland Canal Company was incorporated, its statute stated that Six Nations was entitled to receive compensation if part of the canal passed through their lands, or if there was any damage to their property or possessions as a result. However, their lands were flooded by the canal and compensation was not paid.

In 1890, the Deputy Minister of Justice was supposed to submit the Six Nations’ claim to the flooded lands to the Exchequer Court of Canada (established in 1875 as part of the Supreme Court, but a separate court today). The claim was filed the next month, but nearly 100 years later, in 1987, it was determined that although the claim had been filed it was never placed before the court. To this day, Six Nations is owed compensation for 2,415.6 acres of land flooded by the Welland Canal Company: destruction and unjust treatment foundational to today’s Niagara.

Immigration to Welland

Welland’s Immigrant Population

For approximately 200 years, since the conception and building of the first Welland Canal, the settlement that is now Welland was built by immigration. Some of the first people to come to the area originated in poorhouses and prisons in the UK, and came to Canada to work on the construction of the canal. French and Chinese Canadians came from other parts of the country, and many people immigrated from the US, Ukraine, Italy, and Hungary.

We can get a glimpse of the demographics of Welland residents from the workers who died building the Welland Ship Canal. The following countries of origin are listed for the deceased workers, in order of most to least deaths: Canada, Italy, England, Hungary, Scotland, Ireland, Russia, U.S.A., Austria/Austria-Hungary, Croatia, Poland, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, Finland, India, Newfoundland, Slovakia, and Sweden.

Immigration & Politics

One of the major themes of Welland’s history is the power of unionization, and people coming together in the face of exploitation and discrimination. However, these ideas did not just spring into existence. The immigrant communities that comprised Welland, particularly the Croatians, Hungarians Serbs and Ukrainians, brought with them new political ideas.

Racism & Discrimination

Throughout Welland’s history, various ethnic groups faced racism and discrimination in addition to the brutal working conditions and dismal pay they already contended with. Citizens often felt that immigrants were purposefully misled about the opportunities and wealth available in the region, leading to mass immigration when there was often barely enough to sustain the people who were already there.

Unfortunately, an increase in this thinking was often followed by a rise in racism and discrimination as anger was misdirected at immigrants, a pattern that is still echoed in our society today. In the 1920s one such wave of poverty, job loss and immigration fanned the flames of racism and some citizens attempted to bring the KKK to Welland. Newspapers would often report on certain ethnic groups or immigrants being ‘lazy’ or ‘aggressive’, though most people were unwilling to recognize that racism and discrimination were issues.

Throughout the years, what was really the fault of misleading advertisements, the greed of large corporations, or government policy was routinely blamed on immigrants who were simply seeking a better life for themselves and their families.

The Springfield Plan

In an attempt to combat the rampant discrimination in Welland, minority activists in the 1940s (including the few Jewish Canadians living here) convinced the Ontario Ministry of Education to bring an American anti-discrimination plan, the ‘Springfield Plan’, to Welland.

This plan aimed to teach children tolerance by highlighting minority groups’ contributions to the community. Unfortunately, those who didn’t face discrimination—particularly those of British descent—either refused to recognize that discrimination existed in their community or turned a blind eye to it. The Springfield Plan was so unsuccessful that interviews with Eastern European Welland residents in the 1980s revealed that none of them even remembered the existence of the plan: instead, they remembered the sense of community and belonging they felt in unions.

Chinese Canadians

Plymouth Cordage

In 1917, Plymouth Cordage company had lost many of their workers to better-paid jobs at other factories. They needed to replace these workers, and employed 200 Chinese Canadian workers from other parts of Canada.

Unfortunately, the Chinese employees generally couldn’t get manufacturing jobs or jobs that paid well due to discrimination, so they were willing to work for Plymouth Cordage for the low wages that had driven others away. At the end of the first World War, most of the Chinese labourers left the area.

Empire Cotton Mills (Woods Manufacturing Company)

This situation repeated itself during World War II, when Chinese Canadians from British Columbia were recruited to work part-time at the Woods Manufacturing Company. Again, most left at the end of the war.

French Canadians

“Our central business district is a financial and governmental hub as well as a shopping district. In all parts of the city, fine, new malls and plazas have arisen. Seaway Mall is newest, an all-weather, enclosed giant. Lincoln Plaza is half enclosed, half open—and is half English, half French. Its merchants are bilingual.”

French Canadians have a long history in the Niagara region, which has contributed to the prominent Francophone community that still exists here today. The Welland River, the namesake of the Welland Canal and Welland itself, had been named Chenondac by the French at Fort Niagara, and they mapped and used it for trade and transportation.

Most of the French community in Welland can be traced to the company Empire Cotton Mills, which was bought by a Quebec-based company in 1914. They brought many Francophone families from Quebec to come work in the factory, who settled in Welland permanently and founded French-language Roman Catholic schools.

Italian Canadians

Italian history in Welland is intertwined with the history of the Plymouth Cordage company. When Plymouth Cordage relocated from Plymouth, Massachusetts to Welland, they asked their Italian American employees to join them in the move. They even encouraged these workers to convince their family members to move from Italy to Welland and work at the factory. The company believed that hiring people based on cultural ties and loyalty would encourage company loyalty as well.

British & Irish Canadians

Many of the first immigrants to the Welland region were from the British Isles. Besides being funded partially by English money, the canal was built by many English, Scottish, and Irish workers as well.

Irish people were particularly influential in the region, and there are many mentions of violence and rivalry between Irish Roman Catholics and Irish Protestants which disturbed the peace and frightened locals. The Irish Roman Catholic influence contributed to the religious flavour of the region, added to later by the French Roman Catholics from Quebec.

Hungarian Canadians

“I used to watch Bert Pajzos perform in these Hungarian operettas. They were beautiful. They were dressed in the hussar costumes, and I used to sit there as a young boy with my mouth wide open. I couldn’t understand a word, but the music, and the singing, and the costumes, were just out of this world.” –Mike Bosnich

There has been immigration to Welland from Hungary over many years, which is evidenced today by the existence of community organizations such as Hungarian Hall. Many community members have fondly recalled the operettas that used to be performed in Hungarian Hall.

Mary Jary

One young woman of Hungarian origin, Mary Jary, was a local hero of the Empire Cotton Mill strike. She was born in Saskatchewan to Hungarian immigrants, and was instrumental in the fight for workers’ rights. She travelled throughout Southern Ontario to bring attention to and raise support for the strikers’ goals, and served as a member of the Hungarian-language newspaper and on the central committee of the Hungarian Canadian Workers’ Clubs.

“What do you think of our spirit now? Haven’t we got the light of battle in our eyes?” –Mary Jary

The press named her the ‘Pasionaria of Welland’ after Dolores Ibarruri ‘the passionate one’, a prominent communist figure of the Spanish Civil War.

Ukrainian Canadians

Most of the Ukrainian-descended population in Welland originated in Saskatchewan, and was brought to work part-time at Empire Cotton Mill (the Woods Manufacturing Company then) during World War II. They were influential in the community, with the first branch of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Federation in Canada organized in Crowland in 1916.

A Ukrainian Canadian named Annie Hunka was an important figure in the Page-Hersey strike. Her husband William was one of the leaders of the strike, and was blacklisted in addition to losing his job. This drove Annie to become a member of the negotiating committee that brought the UE to the Electrometallurgical plant in Welland.

Immigration Today

While Welland has a rich history of immigration and the merging of different cultures and ethnicities, this trend has not continued in the same way. Not many foreign-born workers settle in the Niagara region anymore, gravitating instead towards larger, more multicultural cities such as Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver. The people who do settle here are more likely to be refugees, drawn to the region by its proximity to the United States, and the comparatively mild climate and more affordable housing.

Community Voices

Authors Carmela Patrias & Larry Savage

Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage were kind enough to provide us with statements drawn from some of their large body of work on local history.

Questioning the Postwar Compromise

From: “Employers’ Anti-Unionism in Niagara, 1942-1965: Questioning the Postwar Compromise,” Labour/Le Travail, 76 (Fall 2015): 33-77.

Canadian historians have given considerable attention to the use of plant relocation as a management strategy of union avoidance during the period when it was most significant, from the 1970s on. In Welland, and in Niagara, this practice began in the 1950s and early 1960s. In 1961, for example, when Atlas Steels decided to expand its operations Quebec was competing with Ontario to attract the new plant. Although the city of Welland and the Ontario provincial government were offering Atlas incentives to expand locally, those offered by Quebec were more attractive. But as the president of Atlas Steels, George de Young, explained, the chief disincentive in Welland was the attitude of Atlas workers. “I must tell you,” De Young wrote Ellis Morningstar, Welland MPP, concerning the decision to build a plant in Quebec, “Welland labour is in a very poor position.” He went on to explain that the behaviour of Atlas workers during the last contract negotiations was “distinctly discouraging.” (1)

The high cost of labour in Niagara was also one of the reasons for Reliance Electric’s relocation from Welland to Quebec. The closing came in the middle of contract negotiations with the UE. The manager of manufacturing explained that the decision to close the Welland plant was made “because we found it too difficult to compete out of the Welland plant.” (2) Reliance workers and their supporters quickly questioned the veracity of this explanation. The promise of greater profits in Quebec, where wages were significantly lower than in Welland, they maintained, was the real reason behind the company’s move.

1. George de Young to Ellis Morningstar, MPP, 11 October 1961, letter marked “Strictly Personal and Confidential,” Premier Leslie M. Frost general correspondence, RG 3 23, AO.

2.”Reliance Electric to Close Welland Plant as of June 4,” Welland Evening Tribune, 21 May 1964.

Living in a Dying Town: Deindustrialization in Welland

Modified from Union Power, by Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage

More than four decades later, in 2008, the closing of John Deere Welland works in Daine City, marked the final chapter in Welland’s deindustrialization. CAW union local president Tom Napper described what happened:

There were 800 people standing in one of the warehouse-type things with speakers set up, and they brought in one of the big guys from the States, and they proceeded to let our manager make the announcement that we are here today to announce the closure of John Deere Welland Works, and that was how they opened and closed..it was short and sweet. I would have to say that’s probably one of the worst predicaments I’ve witnessed, to look across the room at people that I’ve worked with for 30 years and plus, and their chins actually hit the pavement. As a matter of fact, most people just turned and said, “What…what…what did he say? I couldn’t have heard that right.” They were astonished because actually the mood in the plant…they thought that they were going to be there for an announcement to maybe add another product…because they had been so busy, they were just working seven days a week, they were behind schedule, everything was good. (1)

Although for the previous several decades, Welland had seen its base of heavily unionized industry steadily eroded, having never fully recovered from the deindustrialization precipitated by the introduction of free trade in the late 1980s, the announced closure of the John Deere plant in many ways defied logic. After all, the company was profitable, the product was in demand, and the workforce was both reliable and efficient. Over the years when the company and the union entered into contract talks, management would frequently raise the spectre of plant closure. But the union was certainly not prepared for an actual plant closure. Indeed, the announcement caught workers completely off guard.

For its part, the company told the local media that “the decision is not a reflection of the work or productivity of our employees.” Instead, John Deere blamed the high exchange rate and soaring energy costs. The bottom line, however, was that the company was motivated by greed. It knew it could make more money by closing its profitable Welland plant and opening a new plant in Mexico operated by workers who would earn a fraction of what the company’s Canadian workers were making. The announced closure of the John Deere Plant in Welland sent shock waves through the community and generated national headlines as a stark example of the crisis in deindustrialization facing Canadian workers and their communities.

Thank you for visiting!

The history of Welland’s blue-collar workers is the history of Welland itself. Workers built the canal and the city that sprung up around it; their hard work and tax dollars funded community projects, schools and hospitals; their families contributed to the prosperity and growth of non-industrial business; and their labour organization and push for unionization stood up to the greed of powerful corporations and inspired a nation.

Though it’s true that Welland has faced many challenges in the past decade, the future is bright. Just like the hardworking citizens of the past two hundred years who came together in times of hardship; across ethnic, linguistic and political differences to improve the lives of all, we too have the power to create positive change and overcome today’s challenges.

We want to give a special thank you to the City of Welland and Canadian Heritage, whose generous support made this exhibit possible.

Sources

- The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation by John N. Jackson

- Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara: Union Power (2012) by Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage

- Dear John Documentary by Mark Lammert

- Welland Workers Make History by Fern A. Sayles, 1963

- Passages From The Life…An Italian Woman in Welland, Ontario by Carmela Patrias, from Canadian Woman Studies Volume 8, Number 2

- Welland Canals by Michelle Greenwald

- Welland Ontario’s Springfield Plan: Post-War Canadian Citizenship Training, American Style? by Ruth A. Frager & Carmela Patrias, from Histoire Sociale/Social History vol. L, no.101 (Mai/May 2017) p.113-139

- Immigrants, Communists and Solidarity Unionism in Niagara, c. 1930-1960 by Carmela Patrias, from Labour/Le Travail 82 (Fall 2018): 119-158

- Employers’ Anti-Unionism in Niagara, 1942-1956: Questioning the Postwar Compromise by Carmela Patrias, from Labour/Le Travail, 76 (Fall 2015): 37-77

- Immigrant Workers in Crowland, Ontario, 1930-1935. A nation of immigrants: women, workers, and communities in Canadian history, 1840s-1960s by Carmela Patrias

- Foreigners, Felonies, and Misdemeanours on Niagara’s Industrial Fronteir, 1900-30 by Carmela Patrias. From The Canadian Historical Review, Volume 101, Issue 3, September 2020, p.424-449 (article).

- Morality Among Employees of Atlas Specialty Steels by Murray M. Finklestein, 1989

- A Historical and Descriptive Sketch of the County of Welland by Cruikshank, E.A. Ontario: County Council; 1886.

- Welland 1977, publication by the Welland Chamber of Commerce

- Welland Ontario Canada City Brochure, produced & compiled by the Greater Welland Chamber of Commerce (1971).

- Welland Development Commission 1987 Annual Report

- Welland Development Commission 1988 Annual Report

- Welland Development Commission 1989 Annual Report

- All roads (and canals) lead to a blooming Welland by Adam Bisby. Special to the Globe and Mail, published June 4, 2019.

- Welland: A Former Industrial Power House Guided Tour by Fiona McMurran

- Welland the Good: A Brief Review of the Social and Economic Aspects and Challenges For a Better Tomorrow. Blue Ribbon Task Force Committee Report by Some of the People of Welland for All of the People of Welland, February 2004.

- This is Welland. Published by The Greater Welland Chamber of Commerce in co-operation with the City of Welland.

- Triumph & Tragedy: The Welland Ship Canal. Published by the St.Catharines Museum. Co-editors: Arden Phair, Kathleen Powell. Editorial Assistants: John Burtniak, Dennis Gannon, Robert W. Sears. Content Assistants: Alex Ormston, William J. Stevens. Designer: Irene Romagnoli.

- https://niagaraparks.com/explore/explore-the-niagara/indigenous-culture-in-niagara-region/#:~:text=Oral%20tradition%20and%20archaeological%20evidence,during%20the%20War%20of%201812.

- https://www.ontario.ca/page/map-ontario-treaties-and-reserves

- https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1370372152585/1581293792285#ucls5

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

- https://www.sixnations.ca/LandsResources/cslc6.htm#:~:text=By%20Statute%20of%20January%2019,of%20Six%20Nations%20was%20determined.